by Kate Pound, St. Cloud State

Are you of the mindset “one couldn’t possibly teach or learn earth science online”? I was very firmly in that camp prior to March 2020. Part of my resistance was the fact that preparing and teaching an effective online course involves an incredible amount of time, and I did not feel that it was a worthwhile investment of my time – there just were not enough hours in the day to develop one in addition to my face-to-face teaching. Then, March 2020 and the pandemic, and we had to pivot to teaching all our courses online, with a scant two-week lead time. A sneak view of the outcome: I think it CAN be done effectively, even in the Earth Sciences. There are of course numerous caveats, which include a concept all earth scientists are at one with: Time. Technology and training also play a key role. This summer has provided me with those T’s – I’ll report back on how it worked at the end of the Fall Semester!

CONTEXT

First, let us rewind to March 2020. We made the transition mid-semester, which has some enormous benefits: the class community had already developed, student ‘lab groups’ (based on the table cluster they sat at for lab) had stabilized, and the class ‘routine’ and expectations were clearly established. On the downside, we were all apprehensive and uncertain, about everything. None of us had signed up for online learning or teaching, many had to move or change living situations, at least 20% had poor or limited online access, and we were living on the brink of something unknown, with little in the way of certainty or comfort.

APPROACH

Faculty all responded somewhat differently, so what I am sharing here is the approach I took. It essentially fell into four parts. Part 1- I felt that because the world would know that if a course was taken in Spring 2020 it was somehow compromised, I wanted to focus on student participation and well-being as the key underpinning to what I was going to do. My task was to try and make students feel comfortable and connected, and consequently engaged in their learning. This would be the path to effective learning. Part 2 – I then had to re-evaluate where we were in our course, and which topics needed to be covered, I then needed to figure out a new class/lecture and Lab routine and delivery method that would help all students do their best. Part 3 was grading – I had to figure out how grading would work – students do worry about their grades, and I wanted to be absolutely clear about how I would handle our pivot and change in approach to the calculation and assignment of grades. Part 4 was Technology – I needed to ramp up my understanding and use of technology across a wide range of applications, including the limitations of my home computer. I delivered the course through synchronous Zoom lectures at the usual lecture time; the Zoom lectures were also (see note later) recorded, and available for students to view asynchronously. I gave weekly quizzes in our learning management system (LMS), which is D2L-Brightspace (‘D2L’). Other institutions use Moodle, Canvas, and others. I also ran weekly Labs via Zoom, which were not recorded.

Student Engagement

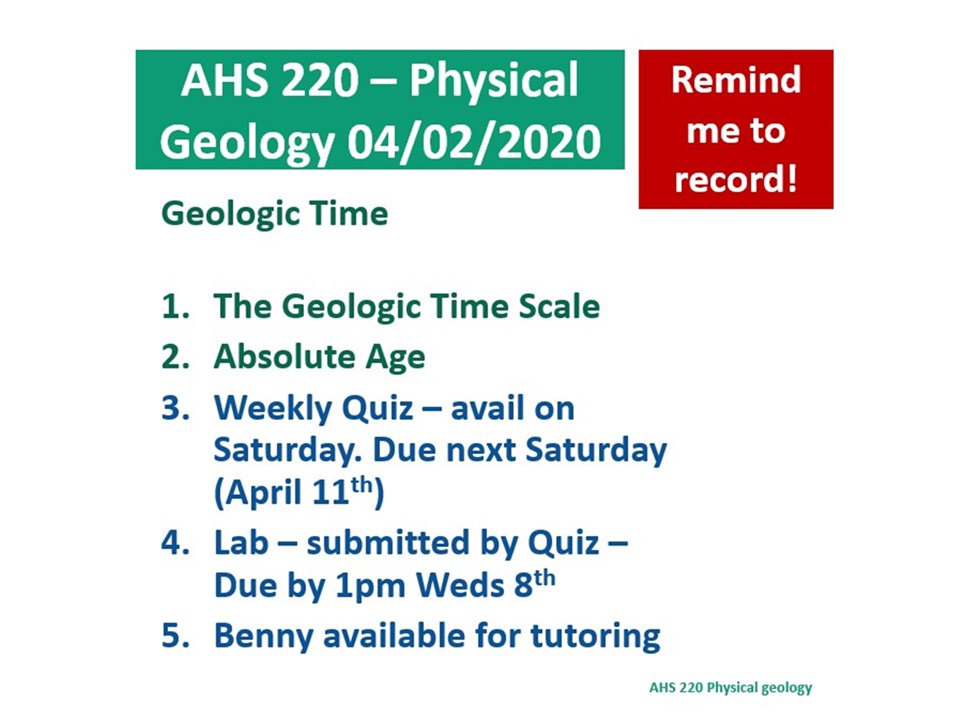

Students wanted to know immediately what my plan was, so I had to make my plan and communicate it to them and let them know that I was available (online) to discuss any concerns. I was concerned about finding that sweet spot between too many emails and postings in our learning management system (they were getting almost daily updates from the University), and not enough. I received some ‘thank-yous’, and I also received some rather combative emails, which I saw to be a consequence of student anxiety – I had to just accept them – and not let them get to me. One bright spot was that I had an awesome TA helping me; Benny is an Earth Science (Geology) AND Earth and Space Science Teaching major, and was already the glue that helped students stick with it – he was extra ‘glue’ in the covid era – he championed student successes and could equally be a task-master as well as a hand-holder. He also helped me by entering the Quizzes into our LMS, and with the online grading. Our class lectures were on Zoom (as were the Labs – more on that later), so when setting the meeting controls I let students join the meeting early (with a password), so that they could chat if they wanted to. By the time I joined, 1-2 minutes before lecture there would usually be some kind of conversation going that I would have cut off. Sometimes students would ask me non-class questions at this time. I also very intentionally let zoom capture the somewhat disorganized nature of my home office and my cats. This was to help the students understand the ‘personal’ aspect of coping with the situation. Yes, I did do some tidying. I deliberately left students to decide how much they wanted to share (i.e. I didn’t require video), both because many had poor connectivity, or were reluctant to share. I made sure at the start of class to remind them about the use of the chat function. Each of my Lab classes was small (one was ~30 students, the other ~12 students) and I knew the students, so I was not worried about the chat or the screen-sharing function being ‘abused,’ so I left them open for student use. My attitude was that if they wanted to have ‘backchannel’ discussions, there are plenty of apps they could use to do that, and that if they were making it to class, they would be focused on class. After saying my hellos as people dribbled in (just like in-person classes, there are always those perpetual latecomers …), I would switch to my powerpoint slides. I was recording my Zoom lectures so that students could always watch them again – or watch them at some other time if childcare or other obligations made attendance difficult. I always started with a slide that gave the day/date, ‘to-do’ items, and the key topics for the lecture. I also tried to find a new cartoon for each day (have you ever tried to search for cartoons only to realize that almost all of them are dealing with some negative aspect of life? It was really hard to find a supply of ‘upbeat’ cartoons that were not political or religious or depressing). I encouraged students to interrupt and ask questions – and they did. I also used the Zoom polls as formative assessment (that essentially means finding out whether they really can apply a concept in a low-stakes situation, vs. high-stakes situations, such as final exams which are called summative assessments). It took a while for me to ‘perfect’ my use of polls. I probably made every mistake I could have (remember to make each question anonymous!), but the students stuck with me. The final part of engagement was making sure that I posted each recorded lecture and powerpoint on our LMS no later than the evening of the class, so students would know they could depend on it being there. I only forgot to press ‘record’ for one lecture, and I never forgot again, because making a recorded powerpoint lecture was incredibly time-consuming, and didn’t always match up exactly to how it went in the synchronous class. At the end of class (as in the beginning of class) I would ‘stick around’ so that students could ask me questions – and they did. The one huge error I made here was to not stop the recording process – some of these conversations involved topics that were related to student’s personal lives and were clearly private. It took me quite a while to figure out how to edit the recordings to remove the personal information that I had accidently recorded; that was very time-consuming – it would probably have been easier if I hadn’t been trying to figure it out remotely on my own.

What Topics, How to Teach Them?

We essentially missed two weeks out of an already-crowded semester. I picked the topics to include in what I called the ‘Coronamester’ (to separate it from our ‘original Spring Semester’ plans) on the basis of how easy or difficult they would be to teach online, based on my experience in the in-person labs. The topics that students typically (but not universally) struggle with are the ones that involve 3-D thinking, which includes topographic contours, topographic profiles, and structural geology. Much to my disappointment, these were the topics that I decided to drop. There were several reasons for my selection – in a face-to-face class (just like in my online class) students arrive with a very broad range of knowledge about how to read topographic maps – from no knowledge at all to those who have used them extensively hunting, hiking, or geocaching). ‘Teaching’ topographic map reading takes more than one lab, involves using physical models one-one one with students, and while a key skill, is not an earth science ‘concept’ on its own – it is a tool. I dropped the more advanced structural geology (cross sections and maps in complexly folded and faulted rocks) for essentially the same reason – it required work with models, and typically lots of one-on-one time with students. In addition, I couldn’t face the idea of trying to grade work that would be submitted as a JPEG or PDF of a lightly drawn and poorly colored map or cross section that I would likely have challenges ‘seeing.’ It was really hard because I see the 3D thinking and spatial skills as fundamental to training in the earth sciences – but I knew I would not be able to do it justice. This was the hardest decision I had to make. I explained this to the students, and will have some significant catch-up to do when I teach the upper-level Surficial and Glacial Geology and Structural Geology in Fall 2020 (online!).

Having decided on my topics, I had to figure out how to deal with exams. In the end I decided to do away with the second and the final exams, and instead have weekly online quizzes on the topics we were investigating. I came to this decision because I could see how high student anxiety level was, and felt that having an online exam, where I couldn’t be sure that there wasn’t some kind of cheating going on, was not worth it. It was more important to focus on making sure they learned the content, than putting lots of work into an online final exam; it also spread out the assessments, which would help the students’ stress in some ways. Of course there are always students that are adept exam-takers that now couldn’t rely on the exam grades for their overall grade; these students seemed to be less disciplined about taking the weekly quizzes and their grades dropped. In the weekly quizzes I scaffolded a series of questions that allowed them to show me they understood concepts and could apply their understanding to a ‘real-world’ situation. I was very lucky here to be able to get the assistance of my TA (Benny), who helped me put these quizzes into our LMS. For my lectures I found that I had to be very selective and focused about how I dealt with a topic. Because I lacked the immediate in-person feedback (those ‘what are you talking about’ or ‘how does that work’ looks on student faces, or very interesting tangential questions that would take me down unanticipated rabbit holes – but which make a lecture real), I had to plan much better, and have much more organized powerpoints that would fit well into the allotted time. I also found that it took much longer to cover concepts. Thus as I planned I became much more selective about what really was essential. It made me a much better educator; I had to be clear and definitive about what to focus on – which is always hard in the earth sciences where we already live in a transitional zone of many grey areas, and caveats.

The Labs were the hardest part. In the past I always had a paper lab ‘handout’ that students picked up as they entered the geology Lab. They would work on the lab in their table groups (individual work, but they could work on it as a team, with myself and the TA there to help as necessary). I would usually do a short 5 minute introduction, and then do short ‘all-class’ reviews (‘Can you stop what you are doing for a moment, there is an important step I need to explain’) when I realized that there was some universal sticking point. How to translate this into the online world? I had to redo all the labs because students did not have the materials (maps etc.) to work with. I settled on a system where I still had a Lab Handout, which I made available to the students as a pdf or word document the night before the Lab. I wrote the questions on the Lab so that students could print out a paper copy if that was how they worked – or they could just type them in to the word document as they worked through it. They then had to enter their Lab answers into a ‘quiz’ in our LMS. This step was essential because student work is often done in pencil, and may be very hard to read, and I did not want to have to download multiple (poorly) scanned labs. It was much easier for me or my TA to go through the online Lab ‘quizzes’ (where the questions mirrored exactly the questions asked in the Lab handout) and grade them. My aha moment here is that I suspect that there is something about typing a response that makes students consider their responses more clearly than if they had been writing longhand; I was pleased with how articulate they were.

So how did I actually ‘manage’ Zoom Labs? When the lab was supposed to start, I gave a brief introduction/overview of the lab, as usual. Then I manually divided the students into their usual lab groups (using the Zoom ‘breakout groups’). Sometimes, students that made it to lectures did not make it to Labs. I wasn’t fussy about that, as long as they did the work (submitted the Lab ‘quiz’); this meant that sometimes I had to amalgamate Lab groups. Once I had figured out how Zoom technology allowed both me and my TA to jump between groups and visit with them, we just moved between lab groups. I was *REALLY IMPRESSED* with the fact that they mostly were using video, and were actively discussing the lab. The sticking point in the labs was students who would ‘come to lab’, and do it with their lab group, but then fail to enter their Lab responses in the LMS Lab Quiz.

Grading

I divided the Spring Semester into two halves. Pre-Spring Break (=pre-Covid), and post-Spring Break (the ‘Coronamester’). Each part was worth 50% of their grade. I used the component proportions for the pre-covid part (e.g. % contributed by Labs, Exams etc.), and then made a Coronamester grading scheme (Weekly Quizzes, Labs). This seemed to work, although I found that it tested student abilities to work with percentages! The big challenge was creating the Labs and quizzes, and then making them available in the LMS, and then grading them in a timely manner. This was the most-poorly managed part of the endeavor.

Technology

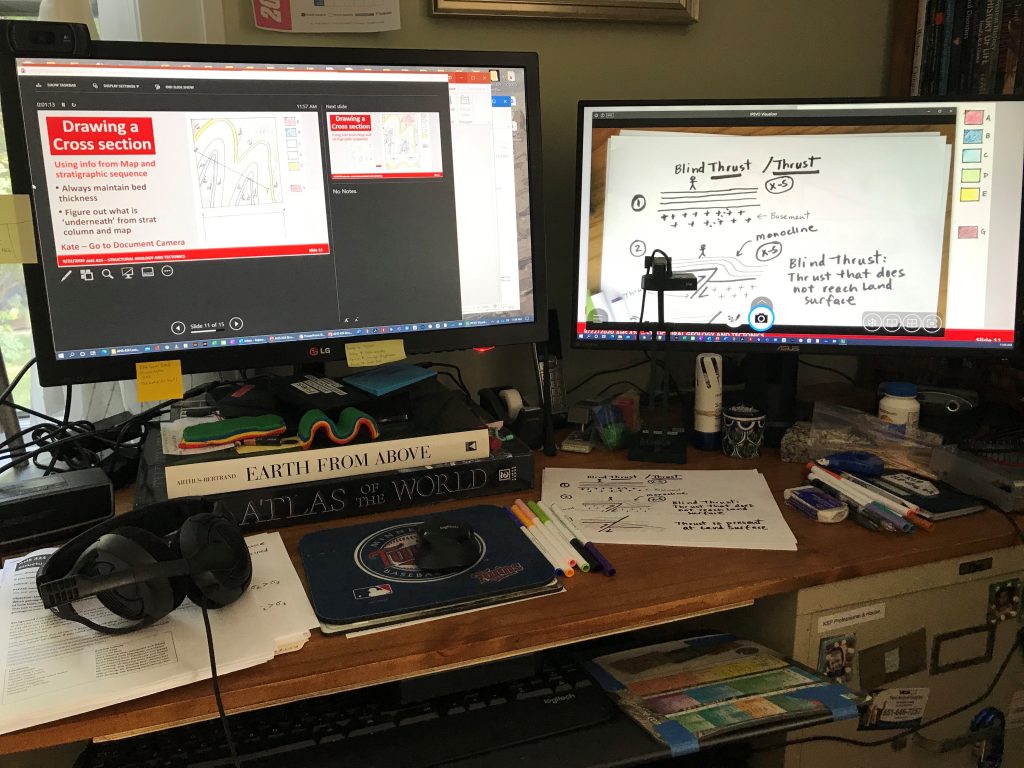

Like most of us, I was flung into using technology that I was not familiar with, on a (home) machine that was not really adequate. I managed to make it work (my January self would have been aghast if it had been told I would be buying a gaming headset!). I never found out whether I was using technology as efficiently as I could be; I had found a way to make it work, and that was all that mattered. Towards the end of the coronamester I got a USB-connected document camera that took a while to figure out – I would have loved to have had that sooner – drawing diagrams on the zoom whiteboard was tedious (I did not have any drawing pad available) and very clunky. The Take-Home

Online teaching can be done and done effectively. The students all knew that this was done as a kind of ‘Hail Mary.’ If you are an employer, and you see a graduate that took a course in Spring 2020, you will have to realize that something will have been sacrificed. On the other hand, the fact that the student stuck with it’ and didn’t withdraw speaks volumes about their determination and engagement. How should you view courses taken online that were not part of the emergency pivot? Courses will always vary in their rigor and efficacy, but I would urge you to treat them equally to in-person courses. I am currently taking an online course in online teaching, and I can attest to the fact that it requires better time-management and dedication than taking an in-person class. I am nervous going into this Fall, because I know the students expect things to be much ‘slicker’ and more professional. I will be better prepared (I hope …), and should be able to better juggle the demands. I am very aware of Zoom burnout, and have many more tools I can use. At the same time, I still want to make it as easy or anxiety-free as possible. I am not going to do the same exams I used to do. I don’t want to stress students out with the hassle of uploading and using yet another app that ‘makes sure they don’t cheat.’ I am currently planning to have a one-day-a-week open lab in a space that can accommodate about 6 students; they can drop in and get help or just chat if they live nearby. Both they and I will be able to ‘bring in’ students that are entirely remote. Once again, it is about the learning, but the learning doesn’t happen without the community. My upper-level students contacted me over the summer. They completely understood going online, but there was a core group that live local to the University, and they asked if they would all be able to meet in our Lecture/Lab room for Zoom ‘lectures’. They recognize that they need and want the presence of other students; some students will still be remote. I’m still figuring out exactly how it is all going to work, but setting things up to best help students learn in the ever-changing environment has to be the priority.

MGWA is committed to developing a just, equitable, and inclusive groundwater community. Click on the button below to read MGWA’s full diversity statement.