By Harvey Thorleifson, Director Minnesota Geological Survey

The people of Minnesota are committed to optimizing our quality of life, through enhanced health, wealth, and safety, while preserving and cherishing our human and natural heritage. We invest our natural, human, and financial resources toward these collective objectives, through efficient and effective mechanisms such as businesses, agencies, and nonprofits. We know good information leads to good decision-making by society, and we are aware that geology is fundamental to groundwater, soil parent materials, engineering, slope stability, and mineral resources.

We therefore understand that comprehensive research, mapping, and monitoring of our geology are required to support modeling, management, and resultant societal benefits. Geological surveys in Minnesota are carried out on a coordinated team basis by Minnesota Geological Survey (MGS), in partnership with agencies such as DNR, MDH, PCA, NRRI and others. Paper maps remain essential, especially MGS/DNR County Geologic Atlases that help people in Counties to better protect their groundwater, and therefore their health and economy.

More and more, though, the product of our work is a coordinated set of databases and collections. The MGS publication database, which is spatial through publication footprints, includes nearly 50,000 pages, and 700 scanned maps, both searchable and web accessible. Our geological mapping increasingly resides, and is used, in a set of progressively more seamless and 3D layered databases, at 1:100,000 and 1:500,000. Geological databases include field observations, geochronology, drillhole data including the immensely important water well database, karst features, as well as sediment texture and lithology. Our geophysical databases include borehole geophysics, gravity, magnetic, rock properties, and soundings. Geochemical databases include groundwater, soil, and soil parent material. Geological collections include geochemical samples, sediment, and thin sections.

However, when we think of geology, many of us think of rocks. And do we have rocks? Yes, we do. The biggest public collection of rocks by far though, is masterfully maintained by DNR at the drill core library in Hibbing; a growing, precious collection of over a million meters of core that urgently needs a new building. (Figure 1. Hibbing Drill Core Library). There also is the large cuttings collection at MGS, built largely through much-appreciated professional collaboration with our water well drilling colleagues.

OK, OK, but what about rocks, the paperweight, baseball-sized kind of rock? Yes, we have those as well, although we at MGS try hard to minimize our collection of rocks. That said, we know that archives of research material are needed to facilitate reproducibility, and also are a precious resource that can allow future research, especially on areas that happen to no longer be accessible.

In the basement of our old building at 2642 University Ave, with help from the US Geological Survey National Geological and Geophysical Data Preservation Program (NGGDPP), we cataloged our rock collection a few years ago. As a result of conservative retention policies, the archive of numbered, labelled specimens linked to a location was only 45,000 specimens! When we moved to our new space at 2609 Territorial Road, we had to fit ourselves into a smaller square footage, as most of us do, to minimize costs. Through our much appreciated partnership with DNR, the MGS rock collection was moved to Hibbing.

But then, it was time for the Department to move out of Pillsbury Hall on the U campus, where MGS was located from 1890 until 1970. (Figure 2. Pillsbury Hall). Many collections and other materials had been moved to the Pillsbury Hall subbasement, which was sealed off in the 1990s due to concerns about asbestos. The last thing to be done to move out of Pillsbury, in autumn 2018, was for a professional abatement crew in protective gear to empty the subbasement, safely discard what could not be cleaned, and retain what could be cleaned.

The result was many very clean crates containing rocks, including many MGS projects from the latter half of the 1900s, a lot of them from the Duluth Complex, consisting of about 6000 rocks. Also, astonishingly, an additional pile of 6000 rocks resulted, derived from cardboard boxes that could not be decontaminated. (Figure 3. Pillsbury subbasement). These rocks had been retained from the surveys of Professor Newton Horace Winchell and his co-workers, carried out from 1878 to 1895. Almost all of the Winchell rocks are well labelled, and linked to locations in early MGS Annual Reports. The Winchell rocks have been sorted into batches according to label code, and are now in storage in Hibbing, along with the crates, so that is a total of about 12,000 rocks salvaged from Pillsbury. (Figure 4. Sorting Winchell rock samples & Figure 5. More samples).

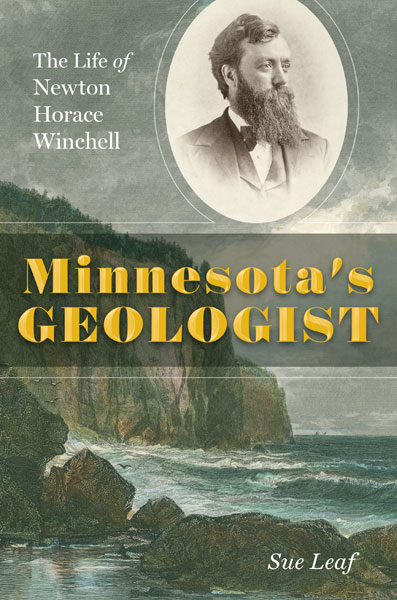

Professor Winchell, Governor Dayton’s uncle, was the first of nine MGS Directors so far. He also went into the Black Hills with General Custer. Back then, we were the Minnesota Geological and Natural History Survey. The Natural History part became the Bell Museum. If you want to learn more about Professor Winchell, and I am sure you do, please purchase a copy of the beautifully written and intensely interesting biography by Sue Leaf, being released this month by UMN Press – Minnesota’s Geologist. (Figure 5. Minnesota’s Geologist). Happy reading!

So, do we have rocks at MGS? Yes, we do, almost 60,000 of them!