While most of our membership is working hard to complete their regular jobs during this difficult time, some of our colleagues have been drafted to work on the pandemic. Hydrologists working for the Minnesota Department of Health have been pulled away from their projects and into a very different world, where they are trained as contact tracers. In a nut-shell, they track the possible movement of the virus from those who have tested positive back to those they may have infected, and thereby head off a larger spread of COVID-19. It’s very different work from what they have ever experienced, and it makes for very interesting reading! We have stories from two of our members, Rich Soule and Justin Blum.

Contact Tracing- the Basics

by Rich Soule, MDH Hydrologist

Although things change every day, our goal is to get information and pass it to those that can benefit from it. The source of information is the “case”, an individual who has tested positive. Cases are interviewed by “case investigators” to gently extract information about who they have been in contact with when they were likely infectious. These are the “contacts” that are “tracked” or “traced” by phone and are informed that they have been exposed and are to go into quarantine for 14 days (as of now, things change fast).

Timing is everything. We think it takes an average of 5-7 days between exposure and symptoms, if any. For the statistics geeks, we think the frequency distribution is log normalish, with a long right hand tail, hence the 14 day quarantine. We think that people are “shedding” viruses for a few days before they are symptomatic, so case investigators focus on the people exposed during those days. It is typically a few days between the test and the case interview. That means by the time a contact tracer can inform the exposed, they have often passed the days where they shed virus and are not yet feeling sick enough to stay home. And there are also a lot of people who never feel sick.

That doesn’t mean we give up, because basically people care and will help each other. The vast majority of people who test positive immediately call everyone they have exposed and tell them to quarantine. They call their workplaces and tell their bosses who they worked next to on their most infectious days. Sometimes they can’t or won’t make that call and a tracker/tracer follows up. For example, the person with a case before a judge who got their results right after a 40 minute face to face conference, or the person in contact with the “cute security guard with the black baseball cap”.

Most of my work has been with businesses. We used to get the names of the exposed and call ourselves, but that added more time than we could afford. Nearly all the time they know who was exposed and have sent them home for the 14 day quarantine. Sometimes I need to point out that we have the same goal: keeping their workers healthy so they can work. Some depend more on PPE than perhaps they should and we brain storm about how to keep the same people working next to each other or in teams to minimize the transmission rate. Sometimes they are working with company policy that is out of date or incorrect (no, cloth masks cannot protect the wearer, but they do protect those around them at least a little.) Mostly, I send emails with translated COVID information (14 languages) and links for employees needing resources to remain in isolation (sick) or quarantine (exposed).

One last thing: DON’T MAKE ME CALL YOU!

An Interim Report from the COVID-19 Front

by Justin Blum, MDH Hydrologist

I was asked to report on what is happening to your fellow groundwater professionals at the Minnesota Department of Health in these unusual times. Because of the ambient time-warp, I am sure that more has elapsed than I can properly account for. Today I have a chance to pause and take a breath, and put together this report. Standard disclaimer: The view from the trenches is necessarily different than that from people who have had no contact with the disease. In addition, please bear in mind that I am not privy to a lot that goes on and usually what information I have has exceeded its sell-by-date.

The MDH as a whole has pivoted to an incident command structure that resembles a military encampment in many ways (without the use of the 24-hour clock). All personnel that can be spared, and inevitably some that can’t, have been reassigned to some aspect of COVID-19 response. The normal coffee-room conversations by which we keep tabs on what people are doing have become Zoom calls. The impact of technology on our work and lives is tremendous. As I’m sure for many of us, Skype and Zoom were mostly used to connect to family before the pandemic. I paid little to no attention to the other platforms. Now, I have to figure out which one of six platforms and three devices on which a call was scheduled, or is demanding my attention; besides, a ridiculous number of computers running simultaneously. But as usual, I digress.

It is all in the numbers

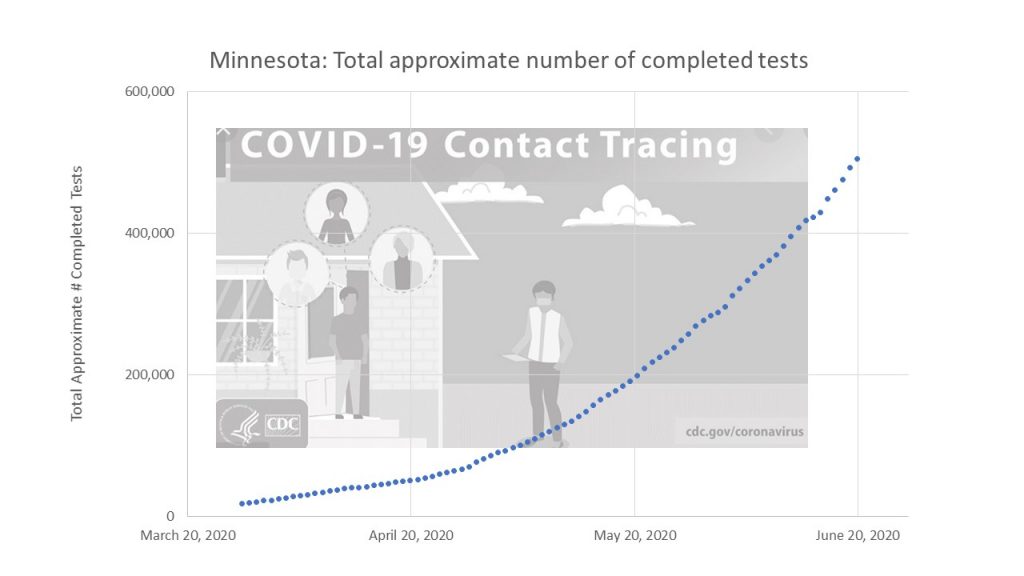

The general rate at which people are being tested in Minnesota has risen to 15,000 tests/day (Figure 1). By law, positive results are reported to the MDH. The data is inspected, cleaned, and added to the queue of cases. The goal is to interview each case within 24-hours of a reported positive test. I am not sure what the positive/day rate has been, but from my own observations it is in the range of 300 to 800 cases/day, based on the daily bounce of the cases. When I started doing case investigations, the database listed between 2,500 and 2,900 cases on any given day. At that time, there was a significant backlog of cases that had not been contacted. Because of the backlog, the number of MDH and local public health staff doing case investigations has gradually increased to about 450 people. On the best day, so far, staff completed over 800 interviews. The most I, personally, have done in one day is seven. Each one takes about an hour to complete. Gradually over the last month, the case queue has shrunk until it was hard to find a case to call. Today, June 10, 2020, is the first day that I have not had to do a case Investigation. As of this morning, the queue was down to fewer than 300. Success! A welcome respite until some unforeseen but totally avoidable disaster overtakes us, yet again. I now have time to take a breath and consider where we have been.

Some recent history

As we in Source Water Protection transitioned to work-at-home in March, several of our coworkers who normally do communications and planning were already working on different aspects of COVID-19 response. The variety of jobs and accompanying responsibility is mind boggling. For instance, John Freitag, one of our wellhead planners, is working on procurement and delivery logistics of PPE supply for health care workers.

Just as work-at-home started, a call went out for volunteers to staff the COVID-19 phone lines. Fellow hydros, Gail Haglund and John Woodside, were initial volunteers. Gail started working the lines answering questions from the general public. John went to a team doing contact tracing of health care workers exposed to COVID-19. As the scope of the epidemic grew, many people from Environmental Health were sucked into the incident command structure (vortex). About three weeks into work-from-home; Amal Djerari, Luke Pickman, myself, and others in drinking water (sanitarians, engineers) were reassigned to case investigations. That meant that we had to venture out of our home bunkers and re-enter the Freeman Building for orientation and training. Later reassignments included Yarta Clemens-Bilaigbakpu to case investigation, and Rich Soule was drafted to a work-place contact tracing team. In all, about two thirds of the Source Water Protection staff who normally work in the Freeman Building in St. Paul are involved with some aspect of the COVID-19 response. I have no idea of the total number of MDH staff who were reassigned to COVID-19 work; but it clearly is many hundreds of people.

After getting familiar with the new job, the requirements of which changed day-to-day, I did case investigations from my desk MDH for a couple of weeks. That changed when the Amazon call-center phone system came on-line, and I could work from anywhere on a secure line that presented ‘State of Minnesota’ for caller-id. I can even route incoming calls to my personal device.

What is my job?

A case investigator does the first step in the process of contact tracing. Specifically, I talk to people that tested positive for the virus in order to:

- Make sure that they are in a safe place, isolated, and have enough food and personal necessities that will allow them to stay isolated while they are sick;

- Determine as best we can when they will be done with isolation; and

- Figure out who they came in contact with before the onset of symptoms – while they were shedding live virus.

Most (but not all) people have figured out that they should not be out and about after symptoms start.

I ask lots of questions from an ‘interview script.’ After I get off the call, the answers go into a database. When the case record is complete, it is removed from the queue. The list of contacts supplied by the infected person goes to various contact tracing teams. Separate teams handle different settings; workplace, congregate care facilities, prison, health care workers, etc. This is a huge undertaking and there are an extraordinary number of moving parts.

The interview script is quite detailed and (to my perspective) intrusive. So, the first item is to make sure that they understand their right to privacy. Their name and medical information are privileged and not shared unless there is a medical need. Most calls I make off the queue roll over to the contact’s voice mail. In that situation, I leave a message identifying myself and requesting a call back to the main case investigation line. If it is picked up, often the person that answers the phone is not the case; it is a wrong number, other family member, etc. Once that is sorted out, and I am talking with the person that tested positive, there often are additional hurdles.

Many times there is a language barrier. Because of the crowded conditions in food processing facilities, COVID-19 has ripped through the worker populations and subsequently their families. Many of the workers are immigrants with limited English. To supplement the small number of multilingual MDH staff, the state has a contract with a company that provides medical interpreters. When someone requests an interpreter, I tell them I will call back. I call the language-line, get an interpreter on-line, and call back to do the interview. Language-line interviews typically take twice as long as normal.

One interview particularly sticks in my memory. I called an individual along with an interpreter, and a torrent of Somali issued from the phone for an extended time. The individual was an 80-something-year-old grandmother who had been isolated by herself in her apartment. She was just happy to have someone to talk to. The interpreter gently kept telling her that I had questions to ask her. Eventually, we established that she was safe and someone brought her meals and checked on her regularly. Her symptoms were manageable, but she was very sad that one of her neighbors had died earlier that day from COVID-19. It was unclear who she might have come in contact with to contract the virus. She had been isolating long enough that she was free to go out in public again, which she was afraid to do. I made sure that she understood how much I appreciated her cooperation and that I wished her good health. Lots of “insh-allah’s” ensued, reminding me of the time I lived in the middle-east. We ended the call. Afterwards, the interpreter and I discussed cultural issues such as respect for elders and the difficulties that isolation causes, particularly with older people. The interpreter had done a particularly good job making this elderly woman comfortable talking with a strange male person. Figure 2, an example of the Tennessen warning in Somali).

Each day brings a different set of stories. A woman who worked in a health care setting was 34 weeks pregnant – with five children already (I could hear much ruckus in the background) — could barely talk from the discomfort of both the illness and pregnancy. A father of a three week-old who tested positive refused the interview (as is his right) over privacy concerns. The daughter whose mother had died that morning from COVID-19. The mother had contracted the virus from a family member at a Mother’s Day get-together.

I find it quite difficult to listen to people in such stressful situations. But listening is required to develop the connections needed to keep moving. Sometimes, cases call back with other questions or issues, and I am happy to help if I can. Most call-backs request a letter to their employer stating that they are cleared to return to work. One was from a father asking if his young son had tested positive. I could not provide that information, but we ended up discussing how the virus had spread through his extended family, linking otherwise separate cases.

This is truly an extraordinary time; both difficult and galvanizing. I am deeply troubled by horrors of recent events and the clearly visible divides in our community at large. At the same time, I am grateful for the opportunity to contribute in a direct and tangible way.

On that positive note, I bid you all kind regards and good health. Reporting from the daylight bunker at the west-metro, Casa-no-COVID-19.